Hanover, 19 June 2023

The first part of this article explored the topic of how a customer journey map is generally created for a customer in the life sciences industry. Within the second part of this post, I will now examine whether the path described is typically followed or what other paths HCPs may take on their journey.

On the basis of three alternative paths that can be taken on an equal footing with the ideal-typical customer journey, I will describe what a customer journey can look like that does not run in the classic order, but only in part or even in a completely different way.

For the sake of simplicity, I will refer to the persona “Linda” developed in the last post in each case and have her experience the three scenarios below. If you don’t already know the persona of Linda from the previous post, click here for more details.

Scenario 1: Proponent, but not yet a customer

„Linda learns about a new therapeutic approach for the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis from an internationally known key opinion leader and speaker (Thomas) at the congress of the DGP, the German Society for Pneumology. He speaks very enthusiastically and authentically about the possibilities that are available. Linda is captivated by his enthusiasm and approaches the speaker after his presentation. In a direct exchange, he also tells Linda the name of the product he is so fascinated by. This is the first time she has heard about our product. She had also not yet associated our company and its products with the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis.

Thomas describes in detail the therapeutic approaches that are possible with it and the way the product works. Since he has accompanied the development in the three clinical phases, he knows the product well enough to convince others with his expert knowledge, which he also succeeds in doing with Linda. Thomas emphasizes the advantages of treatment with our product and refers to the relevant studies or names corresponding sources that confirm his view.

Linda takes her impressions from this conversation with her and then reads up on the subject. To her, the therapy approach with our product also seems innovative, and above all, extremely promising. She finds her first impression confirmed in the sources mentioned by the opinion leader, but also via other materials she comes across during her research. Our product becomes the treatment of choice for her, especially in early stages of pulmonary fibrosis disease. When Linda is subsequently asked about her impressions of the DGP congress at a regional event in her hometown, she convincingly reports on the therapeutic approaches and initial successes possible with our product.

Her appearance as a brand ambassador is so authentic that she in turn arouses the curiosity of other HCPs to use the product. She herself is determined to use the product at the earliest possible opportunity but is certain that her expectations will be met 100%, and she communicates this to her interlocutors in exactly the same way.“

As you can see, the development of a customer journey can also be completely different than expected. When designing different customer journeys, it is important to be creative and to allow for unusual scenarios. Excluding supposedly unrealistic scenarios from the outset can lead in individual cases to having no answers or solutions available for specific unconventional questions. It is also a good idea to allow the developed personas to overlap with other personas, as was done here for the speaker Thomas. In this way, a virtual customer network can be created up to and including a “customer universe” of its own. The models designed in this way are suitable to be applied to two or more personas, since they can be used to adopt different perspectives.

Scenario 2: Innovator or early adopter

„Linda takes part in a series of events designed and organized by our company on the treatment of early-stage pulmonary fibrosis and learns about our new product for the first time in an exchange with other event participants. Linda is immediately convinced by the knowledge imparted, which leads her to use our product at the next available opportunity on a patient who has been diagnosed with pulmonary fibrosis by chance and whose disease is still at a very early stage. As expected, the patient’s response to treatment is positive, and after only a few weeks it becomes clear that the progression of the disease has at least been significantly slowed and that the patient’s limitations in terms of lung volume and quality of life are only marginal and are likely to remain so.

Based on these experiences, Linda reports on the successful use of our product at experience exchanges within her network but also at events she attends. She credibly conveys that, at least in all similar cases, our product is the remedy of choice, virtually without alternative.“

The scenario developed here describes the typical course for so-called early adopters. These are HCPs who quickly become enthusiastic about a topic and implement ideas or prescribe new products accordingly. If the life sciences company succeeds in convincing the HCP to retain or even prefer the newly selected approach, an early adopter or innovator can quickly become a key opinion leader (KOL). As such, he then acts as an ambassador for the product or even the brand, who in turn influences the prescribing behavior of other HCPs because he speaks in favor of the product or life sciences company and inspires others with his enthusiasm.

Scenario 3: A customer migrates away

„Linda first heard about our product from a doctor friend in her network. He described the therapy approach and its possible applications to her. However, he has not yet been able to use the product himself, due to lack of opportunity. She then asked our colleague from the sales force for further information and experience reports, which he sent her by e-mail, but also suggested that she register on our website, for example, to gain access to study results and experience reports. Enchanted by the picture painted, Linda decides to prescribe the product as soon as possible. In fact, shortly thereafter, she is given the opportunity to use our product on a patient who developed pulmonary fibrosis a year ago. This patient’s previous therapy with a competitor’s product did not achieve the results she had hoped for, and which Linda believes would have been possible with our product. Linda discusses a transition to our product with her patient, and as she agrees, she adjusts her therapy accordingly.

Linda calls in on our patient weekly to closely monitor the progress of the therapy, but above all to determine whether our product can confirm her initial impression. In fact, this impression has not been confirmed as she had expected. Although the progression of the disease has slowed down and symptoms have been alleviated, it does not have the effect that Linda had expected based on her documented experiences. She researches further and asks the sales representative about experiences of a similar nature. Since Linda’s questions are highly medical in nature, the sales representative refers her to a colleague on our Medical Science Liaison Team. He then tells her that our product is particularly effective in the early forms of pulmonary fibrosis. In the case of the patient in question, the disease has already progressed to a point where it can no longer be considered an early form. That is the reason why the product is not as effective as expected.

Disillusioned by this realization, Linda does further research and chooses a third-party provider’s product for her patient’s treatment, which now seems more suitable to her with the knowledge she has gained. She again changes the patient’s treatment, but this time with better results. Linda is particularly disappointed that she did not receive appropriate information about our product through the regular channels and that a completely different impression has been created in her mind. Due to this lack of transparency and consistency in the messages placed, she refrains from further prescriptions of our product. Moreover, she informs her colleague (Peter), who also works in her internal medicine practice, of her experience and asks him to consider very carefully whether our product is the right one for the respective patient or to at least consult with her beforehand.“

The purpose of scenarios like the one described here is to identify weaknesses in the key messages placed with the HCP or in the presentation of different patient images (casuistics) and subsequently eliminate them. Inconsistent product or brand messages within a channel or even across different channels can create misconceptions in the customer, resulting in a poor customer experience and even causing a customer to “churn,” as was the case here. Looking for errors in the HCP’s behavior does not help to avoid a wrong impression a customer may get in the first place. Rather, it is advisable to be prepared for such scenarios and to repeatedly evaluate whether the intended impressions stand up to scrutiny from different perspectives. This is the only way to help keep the churn rate as low as possible.

Conclusion

The scenarios described here have one thing in common: they focus on the HCP. The HCP uses various channels for the touchpoints within the customer journeys to obtain information. But is such a perspective even necessary or useful? Are the assumptions made here even relevant for customer acquisition and customer engagement? I will explore these questions surrounding the aspect of customer centricity and other factors related to the customer experience in more depth as part of my next article.

You want more insights?

Check out our other blog articles about customer engagement!

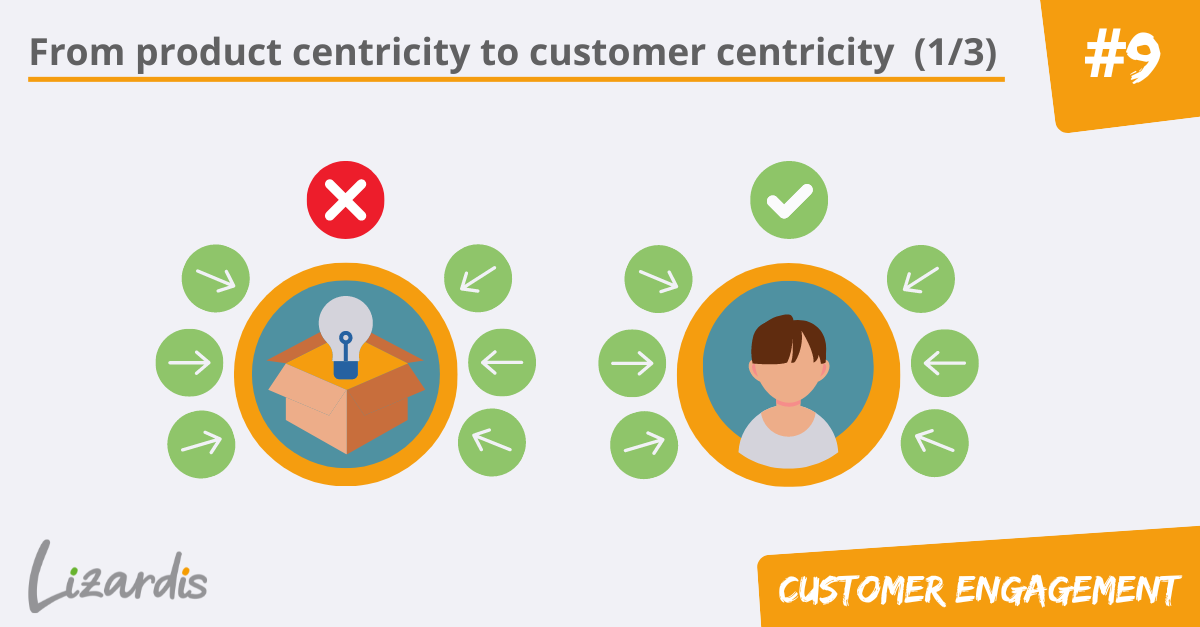

Omnichannel-Management: From product centricity to customer centricity (1/3)

Omnichannel marketing enables the shift from product centricity to customer centricity. Learn more about how it differs from other concepts.

Mapping Life Sciences Customers in the Customer Journey (2/2)

The ideal-typical course of the Customer Journey with phases 1 to 5 not always realistic. Also consider alternative paths that your HPCs follow.

Mapping Life Sciences Customers in the Customer Journey (1/2)

Get to know your customers better by developing customer journey maps for different personas to improve customer engagement.

The Customer Journey in Life Sciences: Taking the customer on a journey – what does that mean?

Develop your contacts along the customer journey into sustainable customers. In our article, we tell you what to look out for in the life sciences environment.